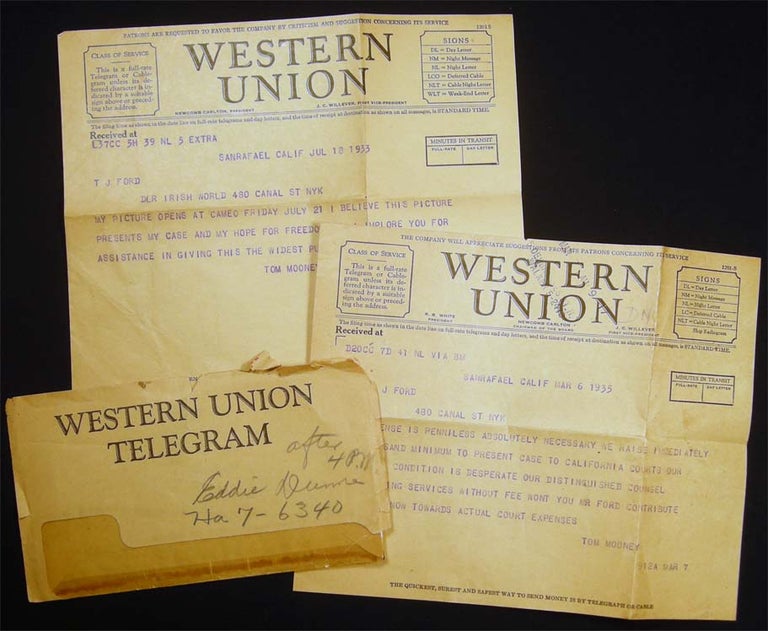

1933 & 1935 Two Telegrams sent from Tom Mooney, Incarcerated at San Quentin Prison in California, sent to Thomas J. Ford of the NY Irish World Newspaper, Requesting Help in his Case.

New York, N.Y. Not Published, 1927. Typed Letters Signed. Not Bound. Very Good. Item #027402

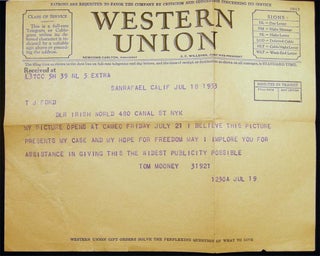

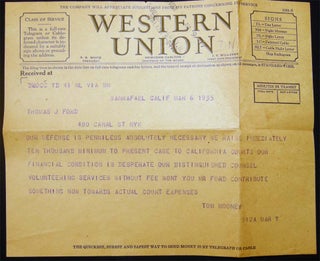

Two Western Union telegrams, sent from the imprisoned Tom Mooney. 1933 July 18 1933. To TJ Ford at the Irish World offices in New York: "My picture opens at Cameo Friday July 21 I believe this picture presents my case and my hope for freedom may I implore you for assistance in giving this the widest publicity possible. Tom Mooney" With Mooney's prisoner number 31921 in the signature line. 1935 March 6 1935 To Thomas J Ford: "Our defense is penniless absolutely necessary we raise immediately ten thousand minimum to present case to California courts our financial condition is desperate our distinguished counsel volunteering services without fee wont you Mr Ford contribute something now towards actual court expenses Tom Mooney" Thomas Joseph Mooney (1882 - 1942) American labor leader. "…By 1916, with World War I in Europe nearly two years old, many Americans were calling for a military build-up. Others, including many labor leaders and radicals, opposed the idea, arguing that it would only hasten the country's entry into what they saw as a corrupt and imperialist war. On 22 July 1916, during the period when Preparedness Day parades were being held throughout the country, a bomb exploded in the midst of San Francisco's parade, killing ten people and wounding forty more. Although there was almost no physical evidence, the press immediately blamed political radicals, while District Attorney Charles M. Fickert concluded that the bomb had been brought to the scene in a suitcase. With encouragement from the private detective at Pacific Gas and Electric who had tracked down Mooney and Billings in 1913 (an earlier case), Fickert quickly arrested both men, along with Mooney's wife and several other people. Billings, who was tried first, was found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. Mooney's trial for first-degree murder followed in January 1917. A rancher named Frank Oxman, who had not appeared in the Billings trial, testified that he had seen both men carrying a suitcase near the bomb scene, and although his statement contradicted other prosecution testimony, Mooney was convicted and sentenced to the gallows. Subsequent investigations discredited Oxman's testimony, but under pressure from local business interests and the Hearst press, Fickert refused to reopen the case. In the meantime, Mooney's wife was tried (without Oxman's testimony) and acquitted.Mooney was saved from execution, but he was still in San Quentin Prison, with no new trial on the horizon. For the next twenty years his supporters struggled to maintain public interest in the case and to win his freedom. They encountered innumerable political and legal obstacles, however, and Mooney's irascibility and distrust made their task more difficult. Nevertheless, they persevered; Frank Walsh, Mooney's attorney from 1923 to 1939, is said to have spent $50,000 of his own money in pursuing various appeals. In 1934 Upton Sinclair, running for governor, promised to set Mooney free if elected; this ray of hope disappeared when Sinclair was defeated. A U.S. Supreme Court decision on one of Mooney's appeals (Mooney v. Holohan, 1935) set important new precedents in federal habeas corpus proceedings, but Mooney remained a prisoner. Mooney failed in a personal appeal to the California state legislature in 1938 and shortly thereafter was rejected for the last time by the U.S. Supreme Court. Finally, in January 1939, Governor Culbert L. Olson granted Mooney a pardon… Mooney did not become a dissident hero by choice; there is no evidence that he had anything to do with the bombing that sent him to prison. Nor was he a hero by nature; his complaints and resentment strained the loyalty of his supporters almost to the breaking point. Nevertheless, his experience forced him into a hero's role, providing the beleaguered labor movement with a martyr and leading many ordinary citizens to conclude that the American system could be very unjust." (Sandra Opdycke in the ANB) With one telegram cover-envelope, worn and with pencil notations. Paper of telegrams & cover browned; old fold lines; in good condition.

Price: $250.00